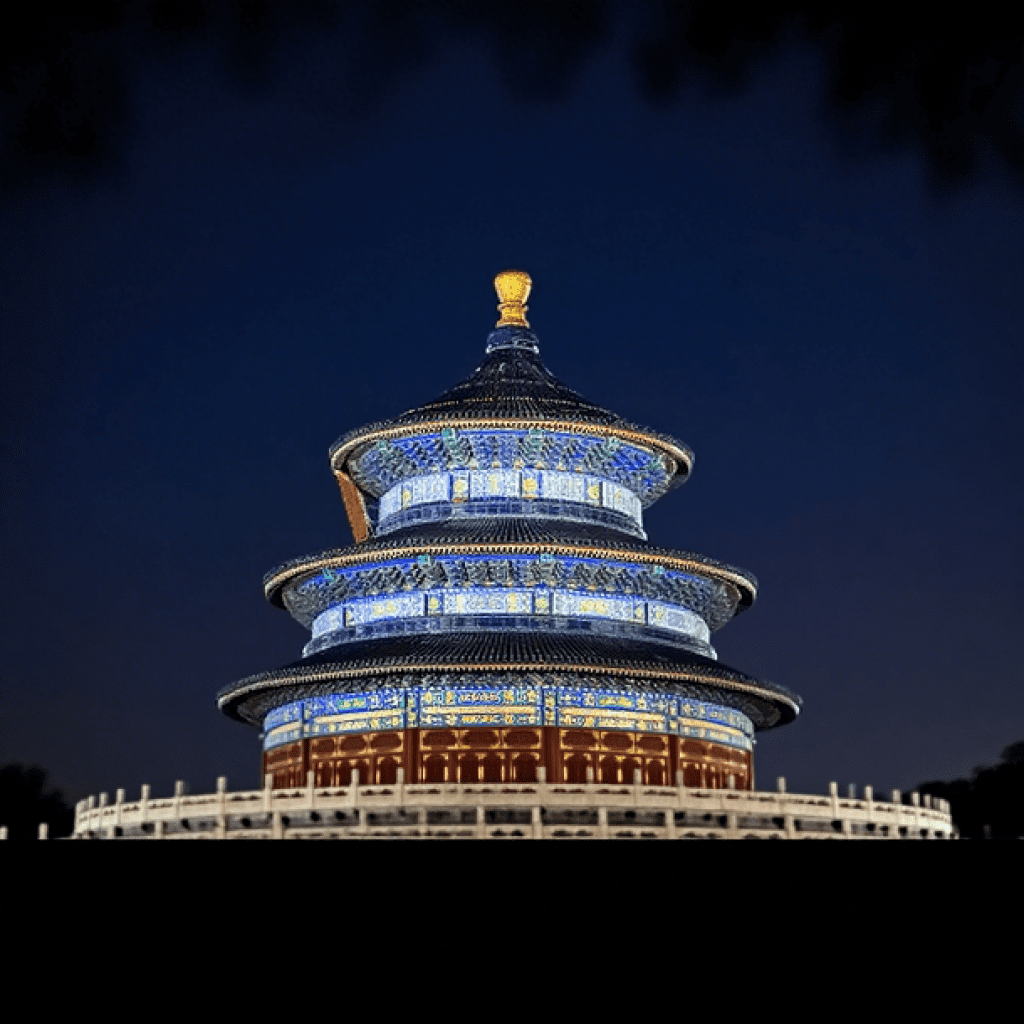

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is not just architecture—it’s a cosmic ritual.

Its triple-eaved circular roof (38m high, 32m wide) rises skyward in blue-glazed tiles, symbolizing Heaven. The square base anchors it to Earth—an echo of Tiān yuán dì fāng (heaven round, earth square).

Inside, 28 timber columns represent the sky: 4 seasons, 12 months, 12 time-hours.

Climbing the triple marble altar was a privilege reserved for the emperor alone. Below, ministers knelt on ranking stones, embodying celestial hierarchy. Here, geometry becomes prayer—space becomes power.

The glazed roof beasts atop palatial ridges signal rank and ritual—nine beasts for the highest authority. Here, architecture enforces cosmic hierarchy.

The Parthenon’s golden ratio and column fluting embody Western ideals of harmony, logic, and civic virtue through perfect proportion.

Unlike rigid symmetry, Suzhou gardens embrace asymmetry and void—where space breathes, and silence speaks. It is a philosophy of absence and flow.

In Northern Song Kaifeng, the city was not a machine of control, but a living organism.

Night markets flourished beyond strict zones, the Bian River carried commerce day and night, and taverns opened their arms to the crowd.

The removal of barriers between residence and commerce, ritual and daily life, reflected a deeply Confucian worldview: cities should serve people, not contain them.

Just as rivers change course to nourish life, Kaifeng flowed with social mobility, cultural vitality, and the intimacy of daily exchange.

Built by the Yuan dynasty, Dadu (modern-day Beijing) was a mandala in stone.

From the main gate to the imperial palace, every structure aligned on the central axis.

This was no coincidence—it was philosophy made architecture.

Unlike the human-centered sprawl of Kaifeng, Dadu embodied the heaven-centered authority of a nomadic empire.

The axis did not flow; it pointed. It said: Power is not among the people—it descends from above.

Because a city is never just a place—it is a story a civilization tells about itself.

Kaifeng whispers the dignity of the commoner; Dadu proclaims the command of the heavens.

By walking through these spaces, we are not just tourists, but readers of the past.

This stone-engraved Song dynasty map divides the world into precise gridlines. At its center lies Yuzhou—the Middle of All Under Heaven.

This is not just geography, but cosmology made visible: a kingdom mapped by divine geometry, where order begins at the center and radiates outward.

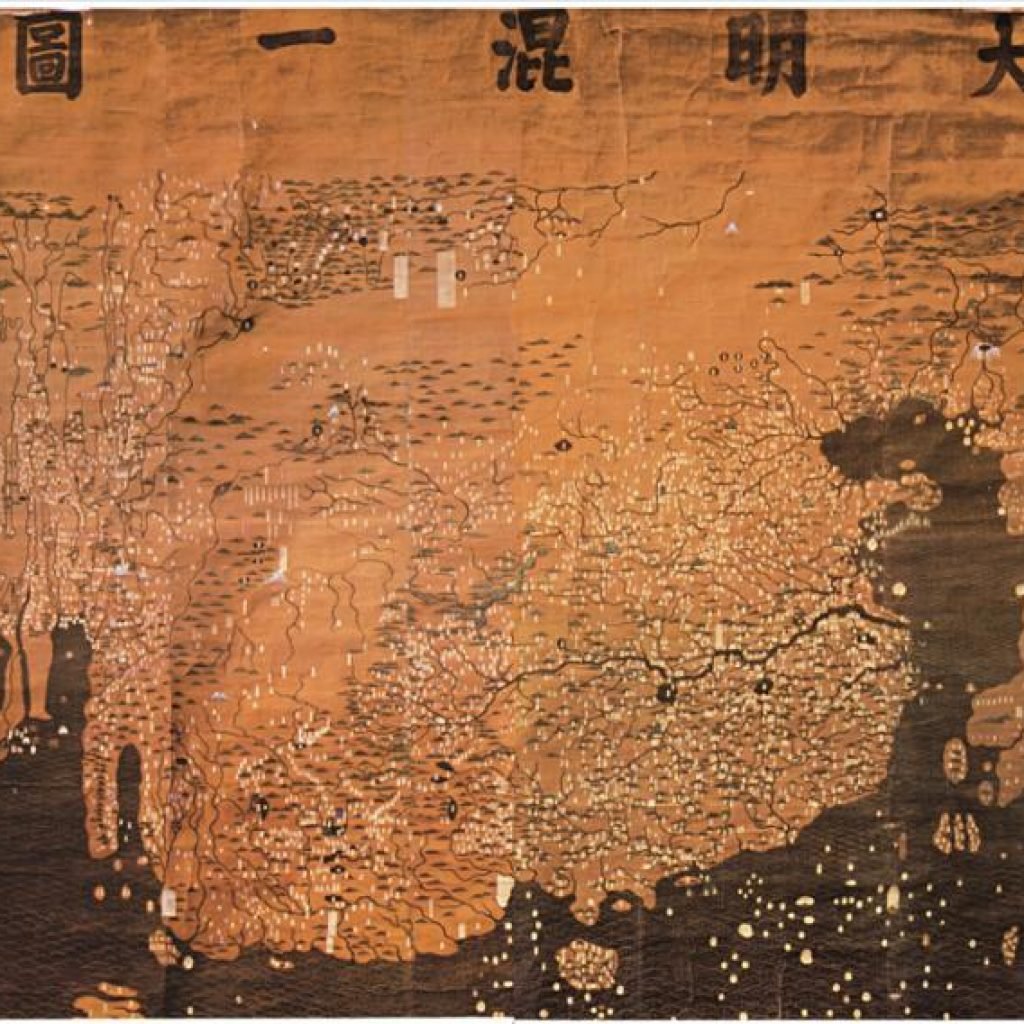

The Da Ming Hun Yi Tu—Map of Ming Unity—depicts China as the dense core of the world, with distant lands like “Wa” (Japan), “Xifan” (Tibet), and “Nüzhen” (Jurchen) placed at the margins.

It’s a visualized tribute system: a cartographic ritual where civilization flows from the center to the periphery.

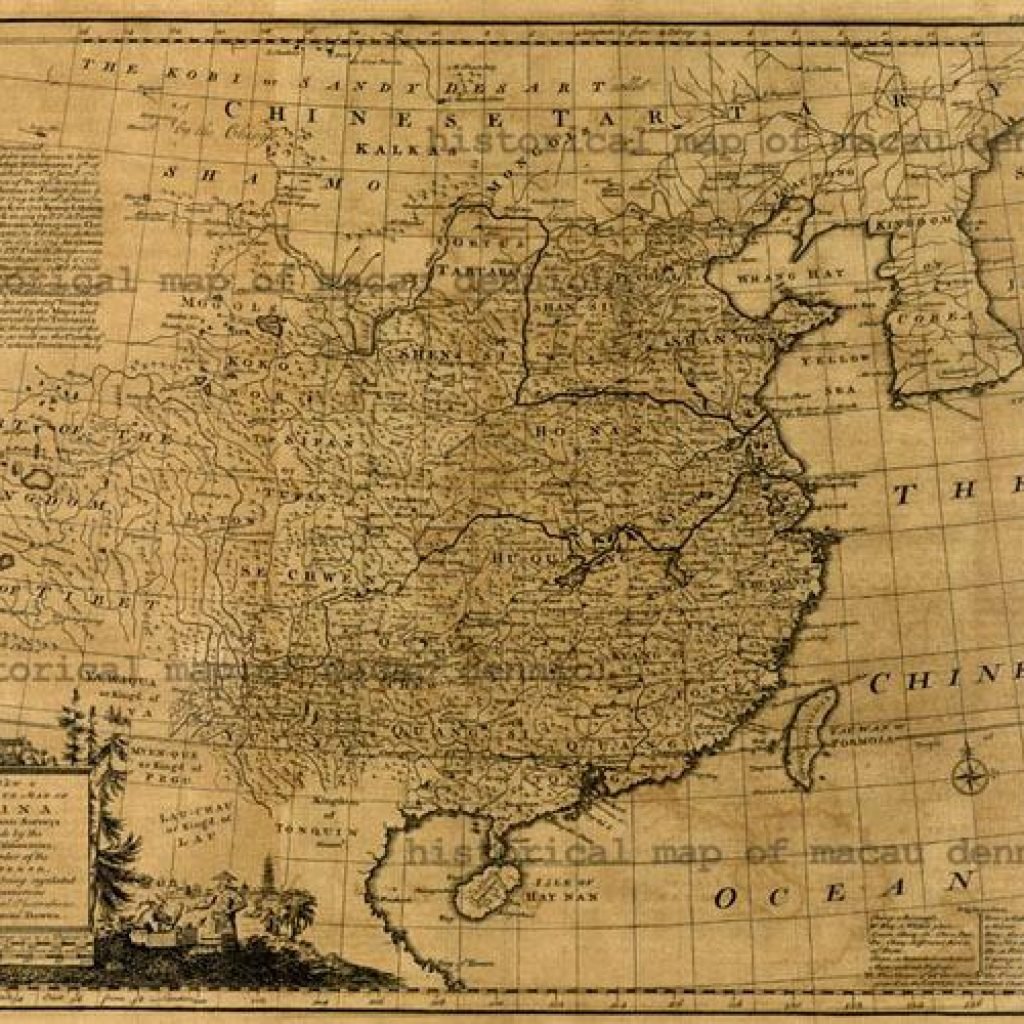

Though based on Western cartographic techniques, this Qing-era map places Beijing at the center of its longitudinal grid.

Empirical accuracy meets imperial imagination—science bends around sovereignty.

The Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests in the Temple of Heaven rises in concentric circles, a triple-tiered altar mirroring the ancient belief: Heaven is round, Earth is square.

Its architectural geometry isn’t just symbolic—it channels the emperor’s role as the Son of Heaven. Each ritual performed here was not merely a ceremony, but a cosmic reenactment: aligning heaven, earth, and man.

To stand beneath its domed vault is to stand at the center of a worldview where harmony depended on symmetry, axis, and ritual form.

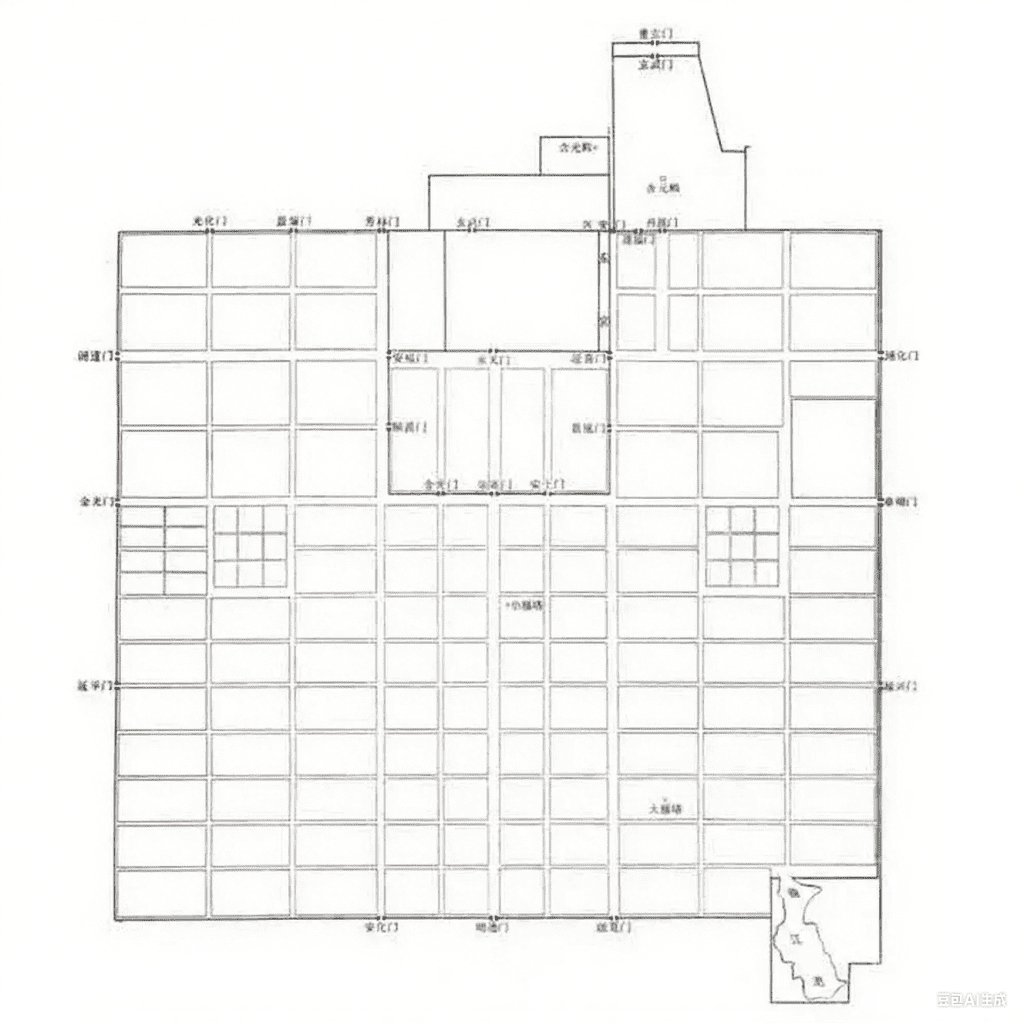

Ancient Chang’an, the Tang dynasty capital, was a living grid—its rectilinear streets and palace walls echoing the square of Earth itself.

From the Taiji Palace to the imperial avenue Zhuque Street, the city was aligned to the cardinal directions, laid out with mathematical precision.

Here, architecture becomes cartography: the very shape of the capital mirrored the moral geometry of rule—order imposed on space, cosmos carved into stone.

From Yongding Gate in the south to the hilltop altar of Jingshan in the north, Beijing’s central axis tells a story written in symmetry.

This invisible line connects temples, gates, and palaces—linking Earth (Yongding Gate), Man (Forbidden City), and Heaven (Jingshan) in ritual alignment.

Even in a modern skyline, this axis still breathes: a spiritual spine holding together a city built not for traffic, but for cosmic coherence.

Ancient Chinese cities were not built—they were mapped.

Mapped by meaning. By Heaven’s roundness, Earth’s squareness, and the axis where the emperor stood.

To walk these cities is to walk through a living cosmogram—etched not only in stone, but in spirit.

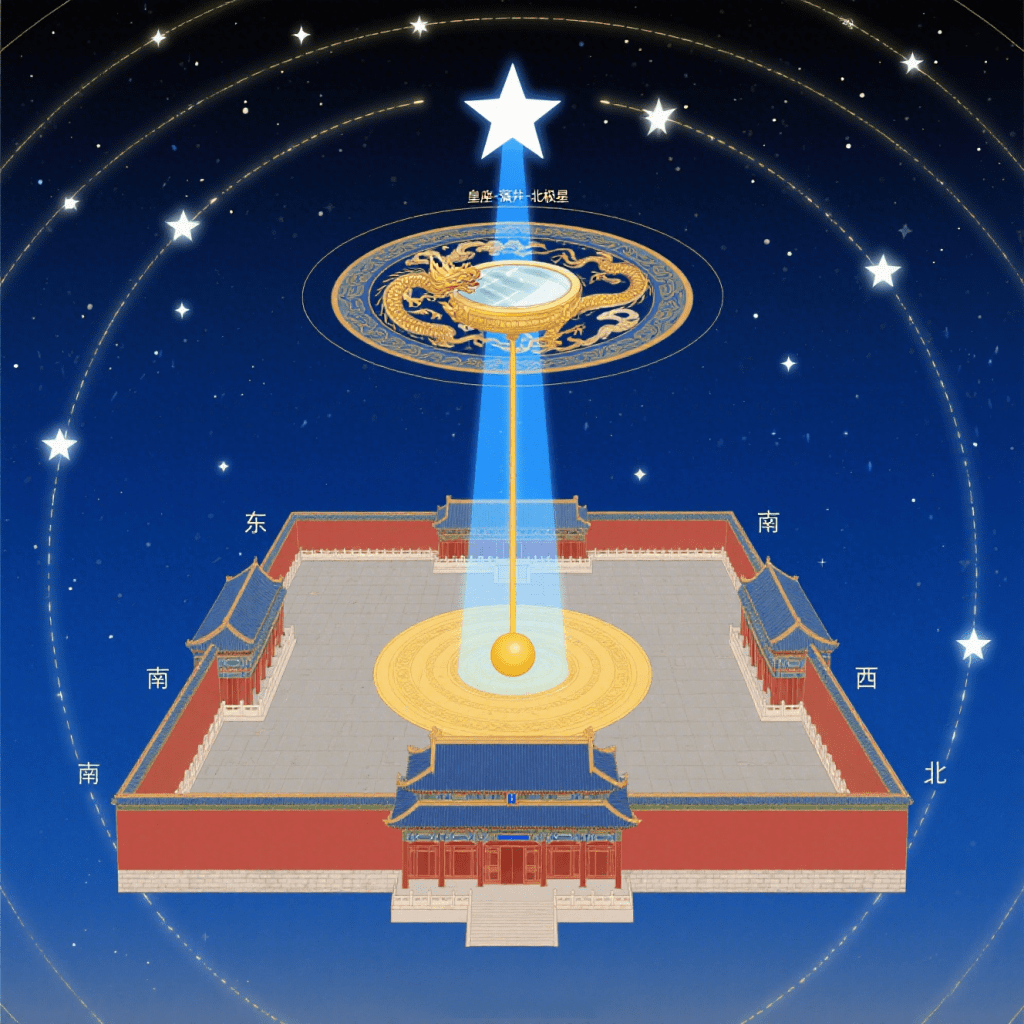

This image captures the invisible yet powerful axis that connected the emperor’s seat to the stars. In the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the dragon-embraced caisson ceiling symbolically opens toward Polaris—the North Star, the celestial anchor of Chinese cosmology. It wasn’t just symbolism—it was sovereignty mapped to the heavens.

To sit on that throne was not merely to rule the land, but to receive the Mandate of Heaven, visually reaffirmed each time one looked up. The structure itself became a celestial compass, turning architecture into a language of divine legitimacy.

Step inside the Temple of Heaven and you’re stepping into an embodied cosmology. The triple-eaved circular roof and the eight-direction layout are not decorative—they are doctrinal. Every beam, every color, every corner echoes the ancient Chinese understanding: Heaven is round, infinite and encompassing; Earth is square, measured and governed.

Here, the caisson ceiling with its golden dragon doesn’t just crown the structure—it summons the sky, placing the visitor beneath the very heart of Heaven. This is not a room. It is a ritual in spatial form. A sacred compass you can walk through.

What you see here is not merely a palace complex—it’s the backbone of an entire worldview. From the Temple of Heaven in the south to Jingshan Hill in the north, a single invisible axis runs through Beijing, with the Forbidden City at its heart.

This line wasn’t accidental. It mirrored the cosmic alignment with Polaris, encoding heavenly order into urban form. To walk down this axis was to move through layers of ritual space, each echoing the emperor’s role as mediator between Heaven and humanity. In this architecture, space became a ceremony—and the city became a cosmic declaration.

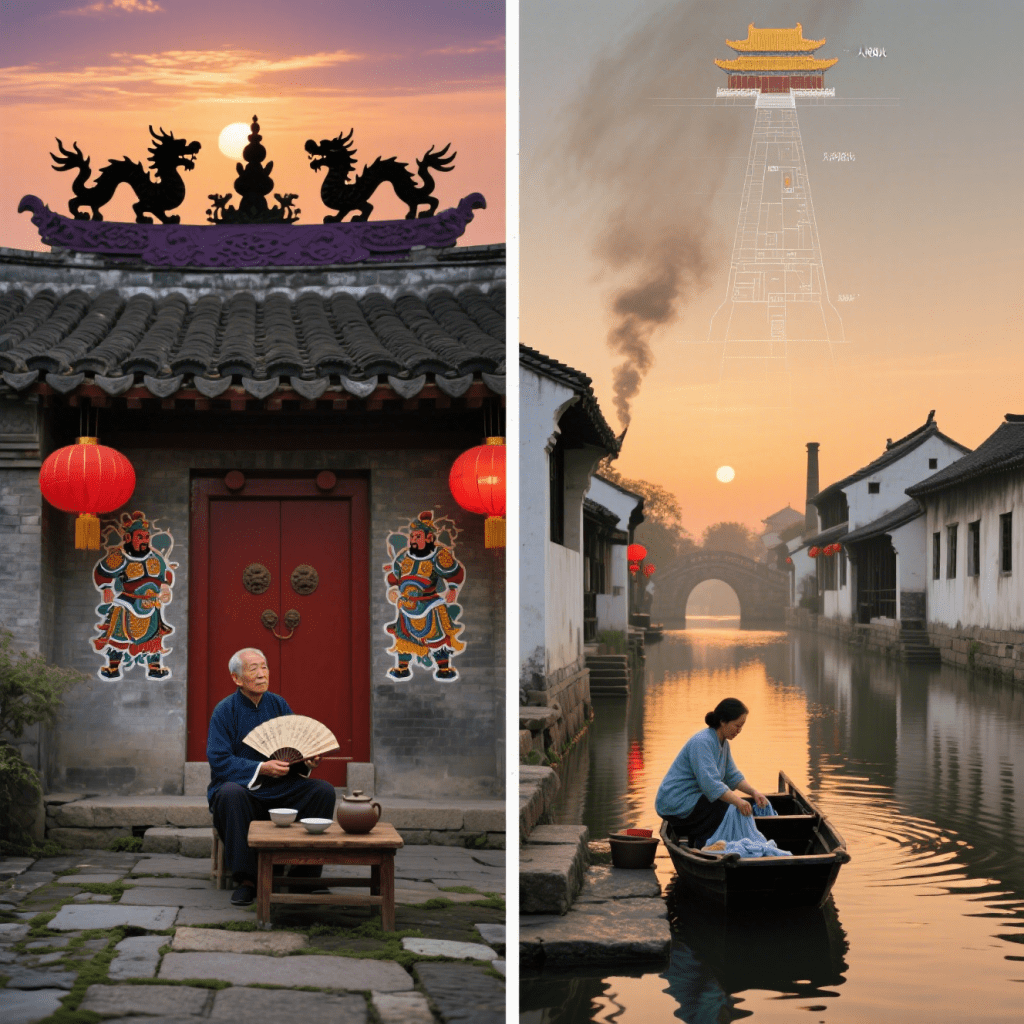

From the Forbidden City’s central axis to the main hall of a courtyard home, the philosophy of “honoring the center” transcends class. Even the simplest residence echoes an unseen geometry — a quiet alignment with the cosmos.

In Jiangnan, homes are never placed arbitrarily. Their orientation, structure, and layout follow the flow of water and principles of geomancy, reflecting reverence for a silent yet omnipresent cosmic order. Beneath the eaves and along the canal lies an unwritten map of the universe.

When palace symbols like ridge beasts and door guardians appear in ordinary alleyways, they shed their imperial authority and become intimate protectors of daily life. Architecture transforms from command into quiet ritual — a presence that guards, guides, and grounds.

Yuan Dadu • 1267

Capital Plan Establishing the Central Axis

Palace City as the Urban Core

Yuan Dadu was the first capital to apply a strict central axis in its urban design. The axis ran through the Palace City and aligned with waterways, reflecting the Yuan dynasty’s vision of spatial order and political authority.

Ming & Qing Central Axis • 1420–1911

From the Forbidden City to the Bell & Drum Towers

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Beijing’s central axis connected the Forbidden City, Jingshan Hill, and the Bell and Drum Towers. This axis unified ceremonial, administrative, and urban life, representing the height of spatial order in Chinese imperial capitals.

Modern Beijing • 21st Century

Extending the Central Axis

Integrating History and Modernity

Modern Beijing has preserved and extended the central axis framework, merging historical heritage with contemporary urban functions. The axis remains both a cultural emblem and the backbone of the city’s vitality.

Through the moon gate, the scene unfolds like a living scroll. In Chinese gardens, architecture frames nature, and nature answers in harmony. What you see is not just a view—it is a philosophy: the unity of man and nature, of reality and imagination.