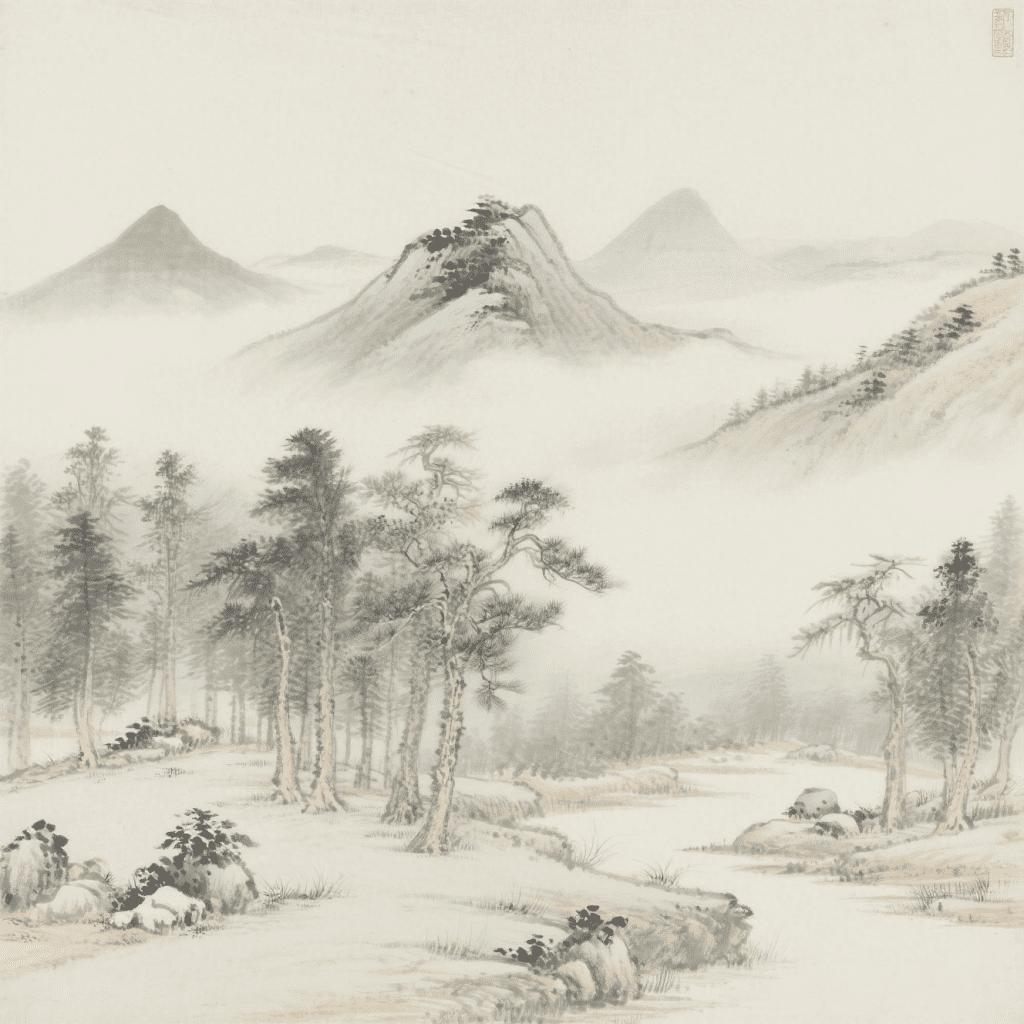

What is Invisible?

Invisible does not mean non-existent; it is the cultural code hidden in the depths.

。

。

Within the square exists the circle; the way of heaven and man resides in its shape.

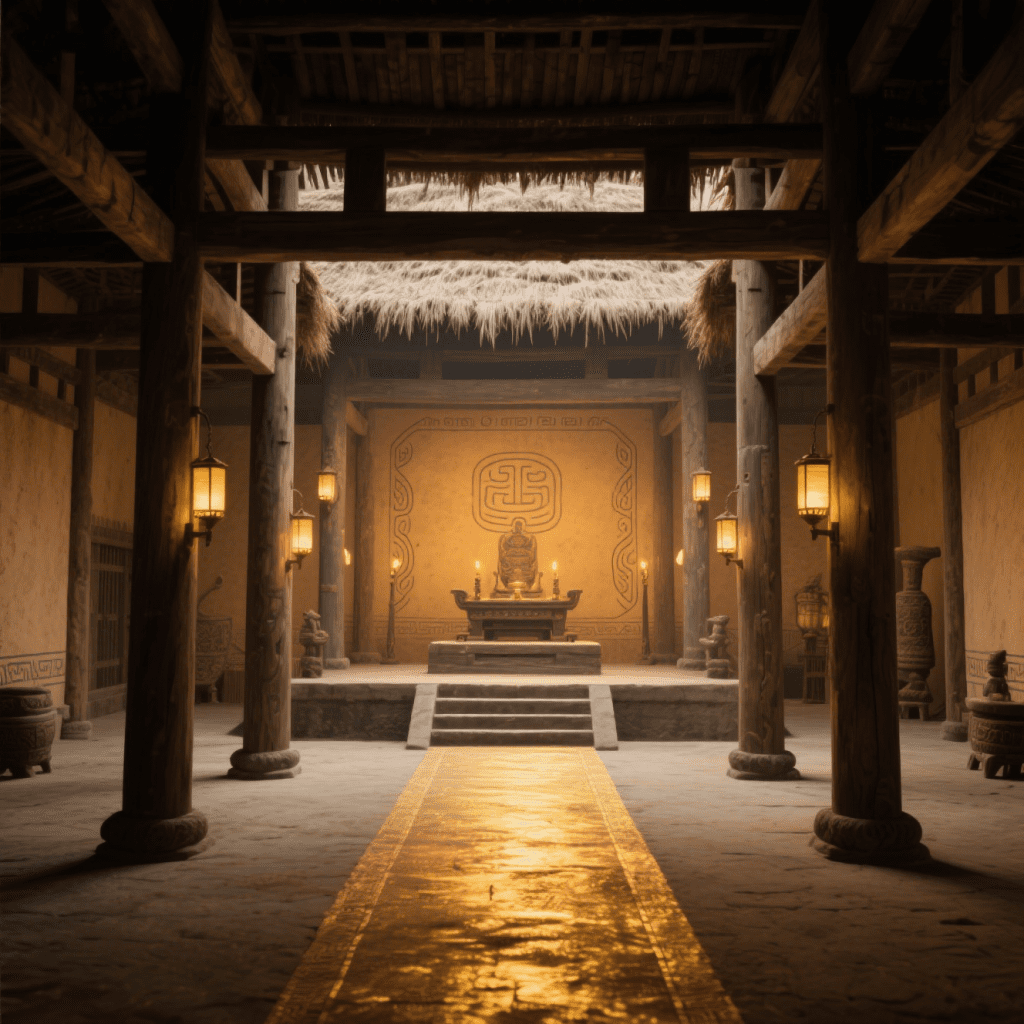

Spaces set the scene for the spirit, and the body serves as the axis of the ritual.

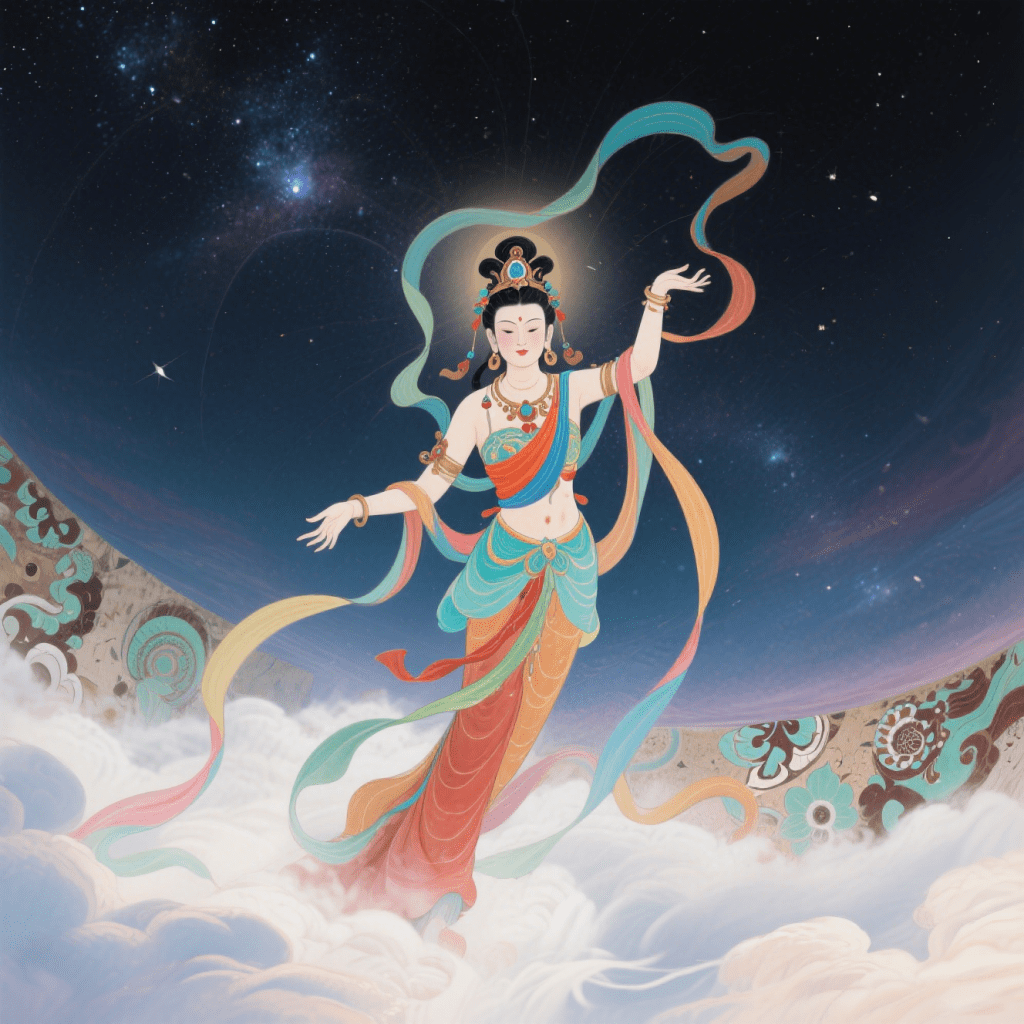

Cosmic vision embedded in murals, thought leaps between the images.

Objects are not simply placed in space — they define it.

In ancient rituals, bronze cauldrons or bells are precisely located along sacred axes.

Their central position transforms architectural space into ritual space.

They anchor meaning, order, and presence.

From the Nine Tripods of Zhou to the music bells of Han,

ritual objects expressed hierarchy through quantity, scale, and materials.

More vessels, finer metal, elevated placement —

the architecture of power was not abstract.

It was cast in bronze.

The shapes of vessels reflect ancient cosmologies:

round heaven and square earth, four directions and five elements.

These designs were not decorative.

They were cosmic diagrams, encoding a worldview into every ritual act.

Stones, vessels, and boundary markers marked the threshold of sacred space.

These were not walls, but symbolic separators —

between inside and outside, sacred and mundane, heaven and earth.

To cross them was to enter another world.

Memory does not live only in words or archives—it breathes in gestures, in clay, in the weight of tools passed through generations. In the hands of the craftsman, memory gains shape.

These marks are not mere decorations—they are records. Each line etched into the vessel’s surface encodes names, hands, rituals. The inscription makes the object speak long after its maker has gone.

Clay remembers the pressure of fingers. Wood retains the rhythm of carving. Material is not passive—it stores intention, friction, failure, mastery. What we hold today is the residue of gestures.

An elder guides a younger hand. Not through speech, but through repetition and feel. Memory is embodied—it flows from muscle to muscle, eye to eye. In this act, memory becomes present again.

Not all memory is obvious. Some remain quiet, buried in dust and damage. But even silence leaves traces. An old pot, forgotten in the corner, holds stories no archive can recover—until we see it again.

From bronze motifs to pyramid silhouettes, from cracked porcelain to Mayan glyphs—objects from ancient civilizations echo across time and geography. They are not just artifacts, but vessels of memory, spirit, and identity. In their silent presence, we hear the heartbeat of humankind.

One cast in bronze to anchor ancestral rites, the other painted for symposiums under olive trees. Though born of different worlds, the Chinese ding and the Greek amphora both embody reverence, rhythm, and ritual. Their shapes are not merely functional—they hold within them philosophies of the sacred.

Why does it matter?

Because form reflects worldview. Through these vessels, we see how civilizations understood divinity, authority, and community.

The fine web of glaze on Chinese porcelain, the ancient fracture lines on Mayan clay—each crack tells a story. These imperfections are not flaws; they are time etched into material. Wounds that speak of age, survival, and silent resilience.

Why does it matter?

Because memory is not always whole. Brokenness can carry beauty, and history often whispers through what’s been mended.

The coiled dragon, the solar deity, the spiraling waves—across China, Egypt, Mesoamerica, and Greece, humans used patterns to narrate time, gods, nature, and fate. These symbols are the oldest shared language—visual poems that transcend translation.

Why does it matter?

Because before we had alphabets, we had meaning inscribed in shape and rhythm. Symbols remind us of our common need to express the sacred.

From China’s Terracotta warriors to Egypt’s sarcophagi, burial rituals reveal how every civilization prepared for eternity. The dead were not forgotten—they were protected, fed, and guided in the next world.

Why does it matter?

Because how we honor death reflects how we value life. These rituals are not about endings, but about belief in continuity, transformation, and the soul’s long journey beyond time.

A Chinese bronze vessel, a Mayan glyph-stone, a Greek amphora, an Egyptian mask—each carries a cosmology. Though oceans apart, these artifacts echo one another in ritual, geometry, and reverence. They do not merely represent culture—they are culture, cast in form.

Why does it matter?

Because civilizations never grew in isolation. We shape vessels, and vessels shape us. When placed side by side, these objects whisper of shared dreams: of origin, of divinity, of what it means to be human.

Across continents, civilizations cast their truths into metal and carved their myths into stone.

The Chinese ding, bearing swirling taotie patterns, and the Mayan solar stele, inscribed with celestial cycles—two objects from worlds apart, yet both vessels of time, power, and prayer.

Why does it matter?

Because when we hold a ritual vessel, we don’t just hold an object—we hold a worldview.

These forms encoded cosmology, sovereignty, and spiritual alignment. They shaped how people understood their place in the universe.

They weren’t made to impress; they were made to remember.