The Three Great Gardens of Suzhou: Cultural Treasures Through the Ages

Suzhou gardens stand as the pinnacle of classical Chinese garden art, and Suzhou’s identity as the "Venice of the East"—with its water town essence—serves as the cultural soil from which these gardens grew. The Humble Administrator’s Garden, Lingering Garden, and Canglang Pavilion are not only UNESCO World Heritage Sites celebrated for their "miniature landscapes in a confined space" but also deeply intertwined with Suzhou’s crisscrossing waterways and water town lifestyles where residents live by the water. These gardens embody the spiritual pursuits of ancient literati while reflecting the vivid charm of water towns—every pavilion and every pond is a testament to the symbiosis between gardens and water towns, holding centuries-old stories of the Jiangnan region.

I. The Humble Administrator’s Garden: A Ming Dynasty Literatus’ Aspiration for "Retreat to Rural Life"

(1) Historical Context: From Frustration in Officialdom to a Legacy Garden

The birth of the Humble Administrator’s Garden is closely tied to the life turning point of a Ming Dynasty official. In 1509 (the 4th year of the Zhengde era of the Ming Dynasty), Wang Xianchen, who had served as a Censor-in-Chief and Investigating Censor, grew disillusioned with the corruption in official circles and resigned due to illness. Returning to Suzhou, he purchased the site of the abandoned "Dahong Temple" in the eastern part of the city—a location adjacent to a tributary of the Pingjiang River, naturally imbued with the moist aura of a water town. Wang took advantage of the water resources to channel water into the garden, spending several years crafting it. He named it the "Humble Administrator’s Garden," drawing inspiration from the Ode to Leisurely Living (“The humble man’s way of governing”). This name, a modest self-reference, implies contempt for the "cunning tactics" in officialdom and also expressed his aspiration to retreat to a rural life amid the scenic beauty of the water town.

Over the following 400 years, the garden underwent multiple changes of ownership and periods of prosperity and decline: In the late Ming Dynasty, the garden was owned by Wen Zhenmeng, the great-grandson of Wen Zhengming (a renowned painter of the "Wu School"). Wen continued the approach of "creating landscapes with water," dredging the garden’s waterways to connect with the external water town system, adding more vitality to the garden. In the early Qing Dynasty, the garden was once divided into three parts: "Guiyuan Tianju" (Return to Garden and Farm Life) in the east, the Humble Administrator’s Garden in the middle, and "Buyuan" (Supplement Garden) in the west. However, each part retained water veins connected to the water town. It was not until the 1950s that the government launched large-scale restoration work, integrating the three parts and restoring the waterway connection to the Pingjiang River. Today’s Humble Administrator’s Garden thus offers both the charm of mountain forests and the elegance of a water town.

(2) Cultural Connotation: Literati Sentiment and Water Town Impressions in "Impressionistic Landscapes"

The cultural core of the Humble Administrator’s Garden lies in the Ming Dynasty literati’s ideal of "expressing emotions through gardens," and the "water" of the water town is the core carrier of this ideal. Wang Xianchen invited his friend Wen Zhengming—representative of the "Wu School of Painting"—to participate in the garden’s design. Taking Suzhou’s water towns as a blueprint, Wen centered the garden around "water" as its soul. The "Yuanxiang Tang" (Hall of Distant Fragrance) in the middle of the garden is its core, surrounded by water on all sides. Pushing open the windows, one can see lotus ponds stretching as far as the eye can see and small boats (modeled after the covered boats of water towns) gliding through the water. In summer, when the lotus breeze carries the fragrance, the ripples stirred by the boat oars and the swaying lotus leaves together form a vivid "water town garden scene." This not only echoes the gentlemanly character described in Zhou Dunyi’s Ode to the Lotus (“emerging unstained from the mud”) but also recreates the leisurely life of literati "sailing on clear waters" in water towns.

The "Yushui Tongzuo Xuan" (Pavilion of Who to Sit With) is a perfect blend of literati elegance and water town charm. Its name is derived from Su Shi’s line: "With whom shall I sit? The bright moon, the clear breeze, and myself." The pavilion, shaped like a fan, stands beside the lake. Sitting here under the moon, one can hear the sound of lake water lapping against the shore (simulating the natural sound of water in water town waterways) and see the night view of the Pingjiang River, connected to the garden’s water system, in the distance. It feels as if one is having a spiritual conversation with Su Shi while overhearing the nightly chatter of water town residents. Additionally, many of the garden’s plaques and couplets hold water town connotations. For example, the "Xiangzhou" (Fragrant Islet) takes its name from the Chu Ci (“Gathering wild mint by the water”), and the islet itself is built to resemble a painted boat in a water town. With its bow facing the garden’s waterway, it makes visitors feel as if they are on Suzhou’s ancient Grand Canal, skillfully linking the garden to water town culture.

II. Lingering Garden: The "Ultimate Exquisiteness" of Qing Dynasty Gardens

(1) Historical Context: From a Private Residence to the "Finest Garden South of the Yangtze"

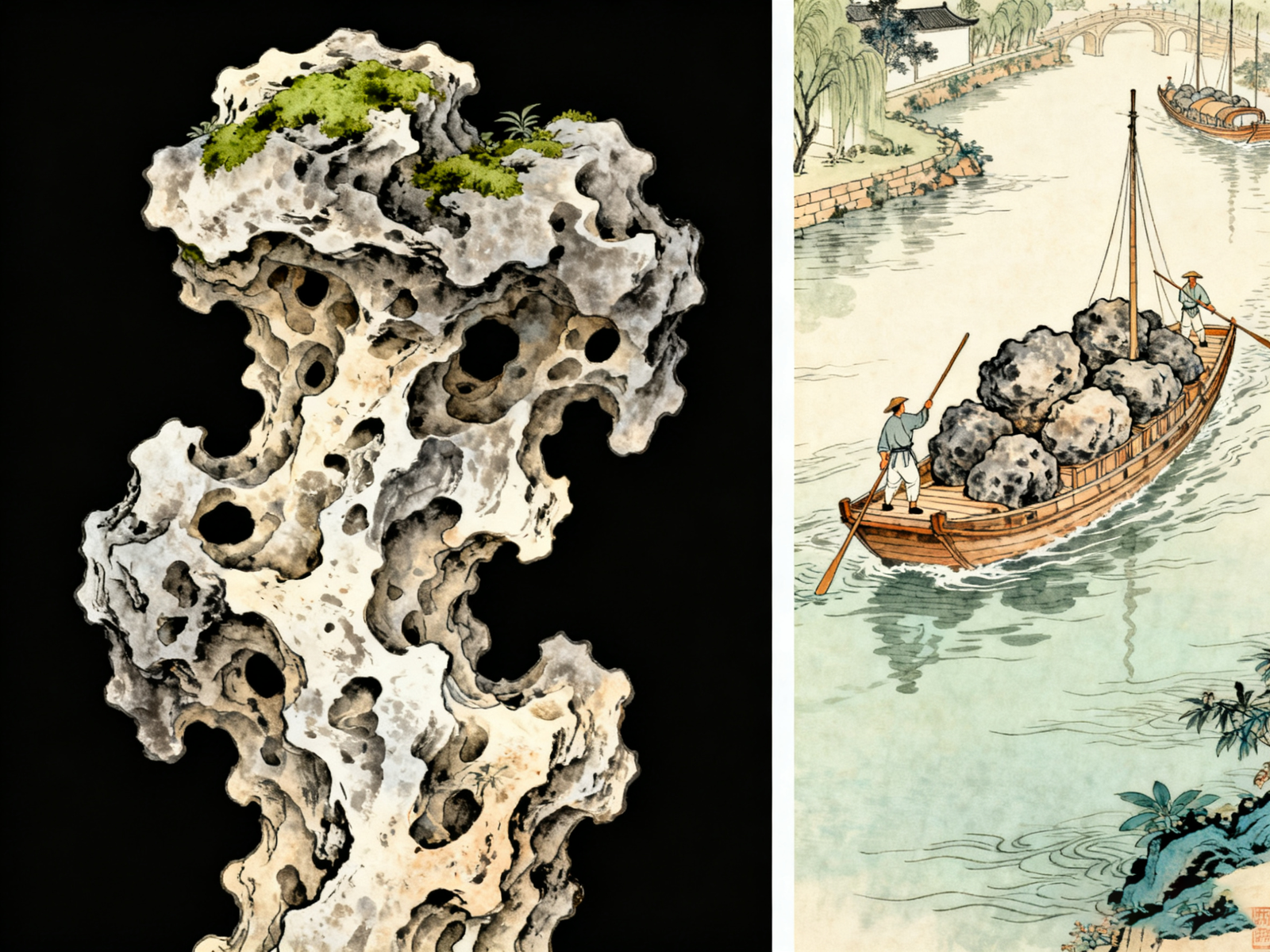

The history of Lingering Garden dates back to 1593 (the 21st year of the Wanli era of the Ming Dynasty), when it was originally the private residence "Dongyuan" (East Garden) of Xu Taishi, who served as Minister of the Imperial Stud. Known for his integrity, Xu resigned and returned to Suzhou, choosing a site outside the Changmen Gate—a bustling area of Suzhou’s water towns, adjacent to the Shantang River, where merchant ships and covered boats came and went constantly. Xu channeled water from the Shantang River into the garden to create "Dongyuan": In addition to exquisite buildings, the garden featured winding waterways connected to external rivers, facilitating daily water use and infusing the garden with the vitality of a water town. The "Guan Yun Feng" (Cloud-Capped Peak) in the garden—a Taihu stone—was sourced by Xu from the ruins of the Song Dynasty’s "Flower and Rock Convoy" (a royal project to collect exotic rocks) and transported back to Suzhou via water town cargo ships, becoming the "treasure of the garden."

During the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty, the garden was owned by Liu Shu, who carried out large-scale renovations: On one hand, he added pavilions, terraces, and collected calligraphy inscriptions from past dynasties, renaming the garden "Hanbi Shanzhuang" (Cold Green Villa), also known as "Liu Garden"; on the other hand, he dredged the garden’s waterways and added a "waterfront corridor" along the banks, modeled after the water town pattern of "houses facing the river, boats moored under windows," allowing visitors to lean on the railings to enjoy the water or sip tea by the water. In the Guangxu era, the merchant Sheng Kang purchased the garden, carried out further renovations and expansions, and renamed it "Lingering Garden" (taking a homophone of "Liu Garden"), implying "preserving this garden for future generations." He also retained the waterway connection to the Shantang River, ensuring the garden remained closely tied to water town life. By the Republic of China era, Lingering Garden was renowned as the "Finest Garden South of the Yangtze" for its "water within the garden, connected to the marketplace."

(2) Cultural Connotation: Craftsmanship and Philosophy in "Miniature Landscapes"

The cultural charm of Lingering Garden lies in its "small yet exquisite" garden art and its integration of water town life wisdom into the philosophy of "harmony between man and nature." The "Guan Yun Feng" is not only the largest Taihu stone in the Jiangnan region but also forms a scenic spot with the "Huanyun Zhao" (Cloud-Washing Pond) below—"rock reflected in water, water winding around rock." The pond is connected to external water town rivers, and its water remains clear throughout the seasons due to natural circulation. This not only meets the Song Dynasty’s criteria for appreciating Taihu stones ("thin, wrinkled, porous, transparent") but also embodies the water town concept of "nourishing landscapes with water": When it rains, water drips from the stone’s crevices into the pond, then flows into the Shantang River via waterways, forming a natural cycle of "garden water → town rivers → Taihu Lake." The ancients described this design as "borrowing the vitality of water to nourish the soul of the garden."

The "changing views with each step" technique in Lingering Garden also embodies observations of water town life: Looking at "Guan Yun Feng" from the "Quxi Lou" (Curved Stream Tower), one can see the rock peak and its reflection in the water, similar to the daily scene in water towns where "people watch bridges from their doorsteps and boats from their windows"; walking down to the "Guan Yun Lou" (Cloud-Capped Tower), the "Ke Ting" (Guest Pavilion) visible through the hollowed-out window lattices resembles the pavilion across the river seen from the lattice windows of water town residences. This design is derived from the refinement of the water town scene of "seeing different views across the river with each step," creating a sense of spaciousness like that of a water town within the limited garden space. Additionally, the "Huanwo Dushu Chu" (Return to My Study) is adjacent to a waterway, with a "waterfront platform" by the window. When literati read here, they could hear the sound of oars gliding over the water and take a boat from the garden’s small pier at any time to go to the Shantang Street market via the waterway, truly realizing the ideal of "living in the garden as living in a water town." This also made Lingering Garden an important venue for Qing Dynasty literati gatherings, where they "gathered friends through literature and conveyed feelings via water."

III. Canglang Pavilion: The "Ancient Soul" of Song Dynasty Gardens

(1) Historical Context: An "Ancient Garden by the Water" Unchanged for millennia

Canglang Pavilion is the oldest surviving garden in Suzhou, and its birth is inherently linked to water town rivers. In 1045 (the 5th year of the Qingli era of the Northern Song Dynasty), Su Shunqin—who was demoted to the position of Suzhou Prefect for supporting Fan Zhongyan’s "Qingli Reforms"—discovered the ruins of the "Former Residence of Qian Yuanyao (Prince of Guangling of the Wuyue Kingdom)" in the southern part of the city. The site was adjacent to the "Fengmen Tang" (a tributary of the ancient Grand Canal), with its pond connected to the canal and willows swaying along the banks, presenting a typical Suzhou water town scene. Su immediately purchased the site, built a pavilion by the water, and named it "Canglang Pavilion" (Green Wave Pavilion), drawing inspiration from the Fisherman in the Chu Ci: “When the water of the Canglang is clear, I can wash my hat tassels; when it is turbid, I can wash my feet.” This name not only expressed his determination not to conform to corrupt conventions but also took the "water" of the water town as his spiritual sustenance.

Unlike the Humble Administrator’s Garden and Lingering Garden, which underwent multiple changes, Canglang Pavilion’s core layout—"taking water as a boundary, building the garden by the water"—has remained unchanged for millennia. After the Song Dynasty, the garden changed owners several times: In the Southern Song Dynasty, it became the residence "Han Garden" of Han Shizhong, a famous general who resisted the Jin Dynasty. Han added a "Wanghe Ting" (River-Viewing Pavilion) along the bank to watch merchant ships on the canal; in the Ming Dynasty, it was converted into the "Dayun An" (Great Cloud Monastery), and monks still retained the waterway for water supply and transportation. However, the basic layout of "building a pavilion by the water and taking mountains as scenery" remained intact. During the Kangxi era of the Qing Dynasty, Governor Song Luo carried out restoration work, not only restoring the name "Canglang Pavilion" but also dredging the waterway connection to the Fengmen Tang. When adding the "Wubai Mingxian Ci" (Shrine of Five Hundred Virtuous Men), he deliberately oriented the shrine’s gate toward the river, implying "letting the spirit of virtuous ancestors spread with the water town rivers," making the garden a carrier of local culture and water town memories.

(2) Cultural Connotation: Literati Integrity and Water Town Essence in "Natural Simplicity"

The cultural essence of Canglang Pavilion lies in its garden concept of "ancient simplicity and returning to nature," which originates from the "simple and natural" aesthetic of Suzhou water town life. The garden has no ornate decorations, relying only on four elements—"mountains, water, pavilions, forests"—to create landscapes, and every element bears the mark of water towns: To enter the garden, one must cross the "Canglang Bridge," a stone arch bridge modeled entirely after the "Zhongshi Bridge" and "Baodai Bridge" of Suzhou’s water towns. The bridge deck is carved with water wave patterns, and below it is a pond connected to the Fengmen Tang. The willows and lotus flowers planted along the bank are the most common plants in water towns—In spring, willow catkins fall on the water and drift with the current; in summer, lotus flowers reflect the bridge’s shadow, creating a scene where "the water town is the garden, and the garden is the water town."

The "Canglang Pavilion" stands atop an earthen hill, with a couplet handwritten by Su Shunqin carved on its pillars: “The clear wind and bright moon are priceless; the nearby water and distant mountains are full of affection.” This couplet not only praises the garden’s scenery but also reveals the life attitude of water town literati: The clear wind, bright moon, nearby water, and distant mountains are the most ordinary things in water towns, yet they are the most precious "priceless treasures" in the hearts of literati. Among the 594 Suzhou celebrities enshrined in the "Wubai Mingxian Ci," many are closely associated with water towns: Wu Zixu dug the Xuma River, Bai Juyi built the Shantang River, and Fan Zhongyan presided over the dredging of Taihu Lake—their deeds are closely linked to water town water conservancy and water transportation development, making Canglang Pavilion not only a "spiritual landmark" of literati integrity but also a "memory hall" of Suzhou water town culture. For millennia, countless literati have taken boats along the garden’s waterway to pay tribute to these virtuous ancestors, experiencing the joy of "boating on water, wandering in a painting." As Wen Zhengming wrote in his Notes on Canglang Pavilion during the Ming Dynasty: “Passing Fengmen Tang by boat, I saw pavilions under the willows, as if in a long-lost Jiangnan dream”—eternally capturing the emotional bond between the garden and the water town.

IV. Symbiosis Between Gardens and Water Towns: Twin Treasures of Suzhou Culture

Suzhou gardens and water towns have never existed in isolation—the "water" of water towns is the lifeblood of gardens, and the "scenery" of gardens is the refinement of water towns. Together, they form the cultural foundation of Suzhou.

From the perspective of garden design techniques, the "water landscape design" of Suzhou gardens is entirely derived from water town experience: The "lotus pond water system" of the Humble Administrator’s Garden imitates the "polder field" pattern of water towns, with sluice gates to control water levels, ensuring water supply for the garden while preventing floods; the "winding water corridor" of Lingering Garden mimics the "riverfront streets" of water towns, allowing visitors to walk along the water as if strolling in a water town; the "waterfront shore" of Canglang Pavilion directly adopts the construction method of "waterfront residences" in water towns, with "waterproof stone foundations" at the bottom of walls to prevent water erosion. It can be said that without the water conservancy wisdom of Suzhou’s water towns, there would be no "living water circulation and evergreen landscapes" in the gardens.

From the perspective of cultural spirit, gardens and water towns have jointly shaped the character of Suzhou’s literati: The "tolerance" of water towns taught literati to "adapt to circumstances," as seen in Wang Xianchen finding peace in retirement in the water town; the "vivacity" of water towns infused literati’s creations with poetic charm, as seen in Su Shunqin writing the poem “A path winds around the quiet mountain, yet it stands in the midst of the city” by Canglang Pavilion; in turn, the "elegance" of gardens elevated the cultural taste of water towns, transforming Suzhou’s water towns from "practical shipping hubs" into "spiritual homes for literati." To this day, Suzhou residents still maintain this "symbiotic life between gardens and water": In the morning, some practice tai chi by the garden ponds while others row boats on the water town rivers; in the evening, the garden lights reflect on the water, mingling with the lanterns of water town households—creating the most charming scenery of Suzhou.

Conclusion

The impressionistic style of the Humble Administrator’s Garden (Ming Dynasty), the exquisite craftsmanship of Lingering Garden (Qing Dynasty), and the ancient simplicity of Canglang Pavilion (Song Dynasty) each represent the artistic peak of Suzhou gardens in different eras. Running through all of them is the unchanging cultural gene of Suzhou’s water towns.

For those who wish to fully immerse themselves in the charm of Suzhou’s gardens and the broader Jiangnan culture, consider exploring curated tours that combine garden visits with other regional highlights—such as the 7-day "Jiangnan Tea & Gardens: Shanghai–Suzhou–Hangzhou" tour available at https://chinatraveldirect.com/st_activity/jiangnan-gardens-tea-shanghai-suzhou-hangzhou-tour/. This tour offers guided visits to UNESCO-listed gardens, Longjing tea picking experiences, and intimate cultural performances, providing a comprehensive way to experience the essence of Jiangnan’s gardens, water towns, and traditions.

Comment (0)